|

| © Copyright Peter Crawford 2015 |

ИСКУССТВО СССР

советский социалистический реализм

(Soviet Socialist Realism)

Socialist realism is a style of realistic art that was developed in the Soviet Union and became a dominant style in various other socialist countries.

Socialist realism is characterized by the glorified depiction of communist values, such as the emancipation of the proletariat, in a realistic manner.

Although related, it should not be confused with social realism, a broader type of art that realistically depicts subjects of social concern.

Socialist realism was the predominant form of art in the Soviet Union from its development in the early 1920s to its eventual fall from popularity in the late 1960s.

The Development of Soviet Social Realism

Socialist realism was developed by many thousands of artists, across a diverse empire, over several decades.

Early examples of realism in Russian art include the work of the Peredvizhnikis and Ilya Yefimovich Repin (see above).

While these works do not have the same political connotation, they exhibit the techniques exercised by their successors.

After the Bolsheviks took control of Russia on October 25, 1917 there was a marked shift in artistic styles.

There had been a short period of artistic exploration, in the time between the fall of the Tsar and the rise of the Bolsheviks.

In 1917 Russian artists began to return to more traditional forms of art and painting.

|

| Анато́лий Васи́льевич Лунача́рский (Anatoly Vasilyevich Lunacharsky) |

Shortly after the Bolsheviks took control, Anatoly Lunacharsky was appointed as head of Narkompros, the People's Commissariat for Enlightenment.

This put Lunacharsky in the position of deciding the direction of art in the newly created Soviet state.

Lunacharsky created a system of aesthetics, based on the human body, that would become the main component of socialist realism for decades to come.

He believed (correctly) that "the sight of a healthy body, intelligent face or friendly smile was essentially life-enhancing."

He concluded that art had a direct effect on the human organism, and under the right circumstances that effect could be positive.

By depicting "the perfect person" (New Soviet Man), Lunacharsky believed art could educate citizens on how to be the perfect Soviets.

Анато́лий Васи́льевич Лунача́рский, (Anatoly Vasilyevich Lunacharsky - November 23 [O.S. November 11] 1875 – December 26, 1933) was a Russian Marxist revolutionary, and the first Soviet People's Commissar of Education, responsible for culture and education. He was active as an art critic and journalist throughout his career. Lunacharsky helped his former colleague, Alexander Bogdanov, found a semi-independent proletarian art movement, 'Proletkult'. Lunacharsky was known as an art connoisseur and a critic. He had been interested in philosophy (not only Marxist dialectics) since he was a student (for instance, he was fond of the ideas of Fichte, Nietzsche, Avenarius). He could read six modern languages and two dead ones. Lunacharsky corresponded with H. G. Wells, Bernard Shaw, and Romain Rolland

The Debate within Soviet Art

There were two main groups debating the fate of Soviet art - 'futurists' and 'traditionalists'.

Russian Futurists, many of whom had been creating 'abstract' art before the Bolsheviks, believed communism required a complete rupture from the past, and therefore so did Soviet art.

Traditionalists believed in the importance of realistic representations of everyday life.

Under Lenin's rule, and the New Economic Policy, there was a certain amount of private commercial enterprise, allowing both the 'futurist' and the traditionalist to produce their art for individuals with capital.

By 1928, the Soviet government had enough strength and authority to end private enterprises, thus ending support for fringe groups such as the 'futurists'.

At this point, although the term 'socialist realism' was not being used, its defining characteristics became the norm.

The first time the term 'socialist realism' was officially used was in 1932.

|

| Ио́сиф Виссарио́нович Ста́лин Iosif Vissarionovich Stalin © Copyright Zac Sawyer 2015 |

|

| Алексе́й Макси́мович Пешко́в Maxim Gorky Akseli Gallen Kallela |

The term was settled upon in meetings that included the highest level politicians, including Stalin himself.

Алексе́й Макси́мович Пешко́в (Maxim Gorky), a proponent of literary socialist realism, published a famous article titled 'Socialist Realism' in 1933, and by 1934 the term's etymology was traced (not surprisingly) back to Stalin.

Gorky was active with the emerging Marxist social-democratic movement. He publicly opposed the Tsarist regime, and for a time closely associated himself with Vladimir Lenin and Alexander Bogdanov's Bolshevik wing of the party. For a significant part of his life, he was exiled from Russia and later the Soviet Union. In 1932, he returned to Russia on Joseph Stalin's personal invitation and died in June 1936.

During the Congress of 1934, four guidelines were laid out for socialist realism.

The work must be:

- Proletarian: art relevant to the workers and understandable to them.

- Typical: scenes of everyday life of the people.

- Realistic: in the representational sense.

- Partisan: supportive of the aims of the State and the Party.

The Characteristics of 'Socialist Realism'

'Socialist Realism' had its roots in 'Neoclassicism', and the traditions of realism in Russian literature of the 19th century that described the life of simple people.

It was exemplified by the aesthetic philosophy of Maxim Gorky. 'Socialist Realism' was a product of the Soviet system.

Whereas in market societies professional artists earned their living selling to, or being commissioned by rich individuals or the Church, in Soviet society not only was the market suppressed, there were few if any individuals able to patronize the arts and only one institution – the State itself.

Hence artists became state employees.

As such the State set the parameters for what it employed them to do.

What was expected of the artist was that he/she be formally qualified, and to reach a standard of competence.

The State, after the Congress of 1934, laid down four rules for what became known as "Socialist Realism": The purpose of 'socialist realism' was to produce a popular culture that promoted Soviet ideals.

The party was of the utmost importance, and was always to be favorably featured.

The key concepts that developed assured loyalty to the party, "partiinost'" (party-mindedness), "ideinost" (idea or ideological-content), "klassovost" (class content), "pravdivost" (truthfulness).

There was a prevailing sense of optimism; 'socialist realism's' function was to show the ideal Soviet society.

Not only was the present gloried, but the future was also supposed to be depicted in an agreeable fashion.

Because the present and the future were constantly idolized, socialist realism had a distinct sense of optimism.

Tragedy and negativity were not permitted, unless they were shown in a different time or place.

This sentiment created what would later be dubbed 'revolutionary romanticism'. 'Revolutionary romanticism' elevated the common worker, whether factory or agricultural, by presenting his life, work, and recreation as admirable.

Its purpose was to show how much the standard of living had improved, thanks to the revolution.

Art was used as educational information.

|

| 'The New Soviet Man (and Woman)' |

Art was also used to show how Soviet citizens should be acting. The ultimate aim was to create what Lenin called "an entirely new type of human being": 'The New Soviet Man'.

Art (especially posters and murals) was a way to instill party values on a massive scale.

Stalin described the socialist realist artists as "engineers of souls".

|

| Flight and New Technology Aleksandr Deineka |

|

| Sunlight, the Body, and Youth Isaak Izrailevich Brodsky |

Common images used in 'Socialist Realism' were flowers (Stalin had a great love for flowers), sunlight, the body, youth, flight, industry, and new technology.

These poetic images were used to show the utopianism of Communism and the Soviet State.

Art became more than an aesthetic pleasure, instead it served a very specific function.

Soviet ideals placed functionality and work above all else, therefore for art to be admired it must serve a purpose.

Georgi Plekhanov, a Marxist theoretician, states that art is only useful if it serves society

"There can be no doubt that art acquired a social significance only in so far as it depicts, evokes, or conveys actions, emotions and events that are of significance to society."

The artist could not, however, portray life just as they saw it; because anything that reflected poorly on Communism had to be omitted.

People who could not be shown as either 'wholly good' or 'wholly evil' could not be used as characters.

This was reflective of the Soviet idea that morality is simple, things are either 'right' or 'wrong'.

This view on morality called for idealism over realism.

Art was filled with health and happiness; paintings showed busy industrial and agricultural scenes, and sculptures depicted workers, sentries, and schoolchildren.

|

| Soviet Socialist Classical Style of Architecture |

In conjunction with the 'Soviet Socialist Classical' style of architecture, 'Socialist Realism' was the officially approved type of art in the Soviet Union for nearly sixty years.

All material goods and means of production belonged to the community as a whole; this included means of producing art, which were also seen as powerful propaganda tools.

So called 'modern art' was rejected by members of the Communist Party, who did not appreciate modern styles such as Impressionism and Cubism, since these movements existed before the revolution, and were thus associated with "decadent bourgeois art".

'Socialist Realism' was, to some extent, a reaction against the adoption of these "decadent" styles.

The disdain for 'decadent art' is similar in many ways to the National Socialist view regarding 'Entartete Kunst'.

It was thought by Lenin (probably quiet correctly), that the non-representative forms of art were not understood by the proletariat, and could therefore not be used by the state for propaganda.

All material goods and means of production belonged to the community as a whole; this included means of producing art, which were also seen as powerful propaganda tools.

So called 'modern art' was rejected by members of the Communist Party, who did not appreciate modern styles such as Impressionism and Cubism, since these movements existed before the revolution, and were thus associated with "decadent bourgeois art".

'Socialist Realism' was, to some extent, a reaction against the adoption of these "decadent" styles.

The disdain for 'decadent art' is similar in many ways to the National Socialist view regarding 'Entartete Kunst'.

It was thought by Lenin (probably quiet correctly), that the non-representative forms of art were not understood by the proletariat, and could therefore not be used by the state for propaganda.

|

| Андре́й Алекса́ндрович Жда́нов Andrei Alexandrovich Zhdanov |

'Socialist Realism' became state policy in 1934, when the First Congress of Soviet Writers met, and Stalin's representative Andrei Zhdanov gave a speech strongly endorsing it as "the official style of Soviet culture".

Андре́й Алекса́ндрович Жда́нов (Andrei Alexandrovich Zhdanov - 26 February [O.S. 14 February] 1896 – 31 August 1948), was a Soviet politician. After World War II, he was thought to be the successor-in-waiting to Joseph Stalin, but Zhdanov predeceased Stalin.

'Soviet Social Realism' was enforced ruthlessly in all spheres of artistic endeavor.

Artists who strayed from the official line were severely punished.

Form and content were often limited, with erotic, religious, abstract, surrealist, and expressionist art being forbidden.

Formal experiments, including internal dialogue, stream of consciousness, nonsense, free-form association, and cut-up were also disallowed.

This was either because they were "decadent", unintelligible to the proletariat, or counter-revolutionary.

'The Unity of the Russian People'

Mikhail Khmelko

Mykhailo Ivanovych Khmelko (Ukrainian: Михайло Іванович Хмелько, 23 October 1919 - 15 January 1996) was a Ukrainian painter, People's Artist of the Ukrainian SSR, and double Stalin prize winner.

Mykhailo Khmelko was born in Kiev. In 1943-1946 he studied at the Kiev State Art Institute under Karp Trokhimenko. In 1948 - 1973 he was a faculty of the same institute.

Khmelko is known for his Socialist Realism paintings: 'Unification of the Ukrainian Lands' (1939-1949), 'Drink A Toast for the Great Russian People' (1947), 'Triumph of the Victorious Motherland' (1949), 'Forever with Moscow. Forever with Russian people' (1951).

MILITARY

'The Storming of the Winter Palace'

'Зимний дворец захвачен'

Владимир Серов

'The Winter Palace is Captured'

Vladimir Serov

'Совет Партисанс'

Митрофан Греков

'Soviet Partisans'

Mitrophan Grekov

'Military Parade in Red Square, 7th November 1941'

Konstantin Yuon

''The Triumph of the Conquering People'

Mikhail Khmelko

Mykhailo Ivanovych Khmelko (Ukrainian: Михайло Іванович Хмелько, 23 October 1919 - 15 January 1996) was a Ukrainian painter, People's Artist of the Ukrainian SSR, and double Stalin prize winner. Mykhailo Khmelko was born in Kiev. In 1943-1946 he studied at the Kiev State Art Institute under Karp Trokhimenko. In 1948 - 1973 he was a faculty of the same institute. Khmelko is known for his Socialist Realism paintings: 'Unification of the Ukrainian Lands' (1939-1949), 'Drink A Toast for the Great Russian People' (1947), 'Triumph of the Victorious Motherland' (1949), 'Forever with Moscow. Forever with Russian people' (1951).

'Marshal G. Zhukov'

P. Korin

'Storming the Sapun Mountain in Sebastopol'

Peter Maltsev

LENIN

'Lenin at the Third KomSoMol Convention'

Aleksandr Lomykin

'ленин ин смольный'

Исаак Израилевич Бродский

'Lenin in Smolny'

Isaak Izrailevich Brodskiy

STALIN

'Leader, Teacher, Friend'

Grigori Shegel

POLITICAL

'Politburo of the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party

at the Eighth Extraordinary Congress of Soviets'

Pavel Malkov

'Сталин витх Форемость Партий Мемберс'

Александр Леонидович Королев

'Stalin with Foremost Party Members - 1948'

Aleksandr Leonidovich Korolev

'Drink A Toast for the Great Russian People'

Mikhail Khmelko

Mykhailo Ivanovych Khmelko (Ukrainian: Михайло Іванович Хмелько, 23 October 1919 - 15 January 1996) was a Ukrainian painter, People's Artist of the Ukrainian SSR, and double Stalin prize winner. Mykhailo Khmelko was born in Kiev. In 1943-1946 he studied at the Kiev State Art Institute under Karp Trokhimenko. In 1948 - 1973 he was a faculty of the same institute. Khmelko is known for his Socialist Realism paintings: 'Unification of the Ukrainian Lands' (1939-1949), 'Drink A Toast for the Great Russian People' (1947), 'Triumph of the Victorious Motherland' (1949), 'Forever with Moscow. Forever with Russian people' (1951).

'Roses for Stalin'

Boris Vladimirski

Boris Eremeevich Vladimirski, (February 27, 1878 – February 12, 1950), was a Soviet painter of the 'Socialist Realism' school. Vladimirski was born in Kiev, Ukraine. He began his artistic studies at age 10, later attending (1906) the Kiev Art College. He exhibited his first painting in 1906. As an official Soviet artist, his work was well received and widely exhibited. His works were aimed at exemplifying the work ethic of the Soviet people; they were displayed in many homes and federal buildings. He is also known for his paintings of prominent public officials.

Boris Eremeevich Vladimirski, (February 27, 1878 – February 12, 1950), was a Soviet painter of the 'Socialist Realism' school. Vladimirski was born in Kiev, Ukraine. He began his artistic studies at age 10, later attending (1906) the Kiev Art College. He exhibited his first painting in 1906. As an official Soviet artist, his work was well received and widely exhibited. His works were aimed at exemplifying the work ethic of the Soviet people; they were displayed in many homes and federal buildings. He is also known for his paintings of prominent public officials.

POLITICAL

'Planning a Parade'

Aleksandr Korolev

'Holiday of the Constitution (1930)'

Isaak Izrailevich Brodsky

GENRE PAINTING

'Посещение моей бабушки'

Александр Лактионов

'Visiting My Grandmother' - 1930

Alexander Laktionov

'Haymaking'

Аркадий Александрович Пластов;

Arkady Alexandrovich Plastov

Arkady Alexandrovich Plastov (born 31 January [O.S. 19 January] 1893 in Prislonikha, Simbirsk Governorate; died 12 May 1972 in Prislonikha, Ulyanovsk Oblast) was a Russian socialist realist painter. Plastov was born into a family of icon painters in the village Prislonikha in the Russian Governorate of Simbirsk. He attended the sculpture department of the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture beginning in 1914. In 1917, he returned to his native village, where he occupied himself with painting, drawing from nature. Starting in 1935, he steps introduces his category painting into the public. According to the strict political-artistic doctrine of the time, which only permits the style of socialist realism, Plastov pictures the life in the Soviet Union, the pervasive building up of socialism. His work is characterized by life in the villages of the Soviet Union, his love for his native land, strong, live pictures and his skills of painting. As the reaction to the events, which moved the population of the Soviet Union at that time, Plastov showed in his pictures, how the village life had changed by the collectivization. As models of the Protagonists of his works Plastov chose characters of his homeland village. The outbreak of World War II inspired new motives for the work of Plastov. He depictured suffering of the Soviet people, work of the women, old people and children on the kolkhoz fields during the war. After the war Plastov kept the values of village life.

'Lunch in the Field'

Vsevolod Petrov-Maslakov

' On Kuban Virgin Land'

Vasili Nechitailo

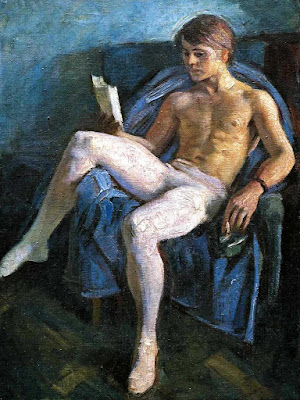

NUDE and SEMI-NUDE

While nudes (particularly female nudes) rarely appear in Soviet Socialist Realist Art - (Stalin had a horror of what he termed 'pornography' - female nudes) - the male nude, or semi-nude, was sometimes acceptable in appropriate circumstances.

Vsevolod Petrov-Maslakov

' On Kuban Virgin Land'

Vasili Nechitailo

NUDE and SEMI-NUDE

While nudes (particularly female nudes) rarely appear in Soviet Socialist Realist Art - (Stalin had a horror of what he termed 'pornography' - female nudes) - the male nude, or semi-nude, was sometimes acceptable in appropriate circumstances.

Мечтатели - 1956

Феллера Романа Наумовича

'Dreamers' 1956

Roman Naumovich Feller

'Future Pilots'

Alexander Deineka

'Советские моряки Дайвинг с военного корабля' - 1933

Алексей Пахомов

Soviet Sailors Diving from a Warship - 1933

Alexei Pakhomov

После битвы - 1942

Александр Дейнека

'After the Battle - 1942'

Alexander Deineka

'Lunch-break in the Donbass'

Alexander Deineka

'Купальщицы'

Александр Дейнека

'Bathers'

Alexander Deineka

'Будущие пилоты'

Александр Дейнека'Future Pilots'

Alexander Deineka

'Советские моряки Дайвинг с военного корабля' - 1933

Алексей Пахомов

Soviet Sailors Diving from a Warship - 1933

Alexei Pakhomov

После битвы - 1942

Александр Дейнека

'After the Battle - 1942'

Alexander Deineka

'Перерыв на обед в Донбассе'

Александр Дейнека

'Lunch-break in the Donbass'

Alexander Deineka

'Купальщицы'

Александр Дейнека

'Bathers'

Alexander Deineka

'После работы'

Александр Дейнека

'After Work'

Alexander Deineka

'Молодой танцовщик балета Чтение'

Михаил Барышников

'Young Male Ballet Dancer Reading'

Mikhail Baryshnikov

______________________________________________

SOVIET ARCHITECTURE

Могила Ленина

Lenin's Tomb - Moscow

Алексе́й Ви́кторович Щу́сев

Алексе́й Ви́кторович Щу́сев

Aleksey Shchusev's 1930 monumental granite structure incorporates some elements from ancient mausoleums, such as the Step Pyramid and the Tomb of Cyrus the Great.

Алексе́й Ви́кторович Щу́сев; (8 October [O.S. 26 September] 1894, 1873 – 24 May 1949) was an acclaimed Russian and Soviet architect, whose works may be regarded as a bridge connecting Revivalist architecture of Imperial Russia with Stalin's Empire Style.

Shchusev was awarded the Stalin Prizes in 1941, 1946, 1948, and posthumously in 1952; the Order of Lenin and other orders and medals.

Мавзолей Ленина - Интерьер

Lenin's Mausoleum - Interior

Саркофаг Ленина

Lenin's Sarcophagus

+-+Great+Russian+Art+-+Soviet+Culture+and+Society+-+Russian+Revolution+-+Peter+Crawford.jpg)

+-+Soviet+Culture+and+Society+-+Russian+Revolution+-+Peter+Crawford.png)